George Henry Hambley (1896-1983)

George Henry Hambley (1896-1983)

My Uncle George enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force at age 18, on the 13 October, 1915 at Camp Sewell (which later became Camp Hughes), near Carberry, MB. He served in France, Belgium, and Germany and was involved in some major battles including Ypres, Mons, Cambrai, and Vimy Ridge.

Some of these battles involved trench warfare where poisonous gas was used. For the remainder of his life, until his death at age 86, his sleep was disrupted from the effects of the gas attacks he had lived through. Sometimes we’d be sitting at the kitchen table talking and Uncle George would suddenly just go to sleep. He’d wake up a few minutes later, not missing a beat in our conversation, as if nothing had happened. I think he felt himself very lucky that this was the worst injury he came home with, after all the horrors of war he’d seen.

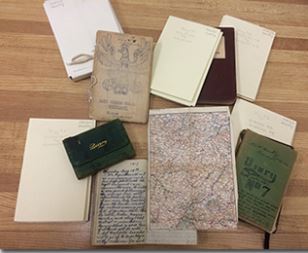

I think what is unusual about my Uncle George, as a veteran, is that he was always willing to talk about his war experiences, unlike a lot of people that lived through WWI and subsequent wars. He would often go, mid-conversation, to his study and get one of the dozen or more diaries he had kept during his time of service and refer to them, recalling men he’d served with, things they had seen and done and talked about. His diaries were rich with detailed text written beautifully with a fountain pen; pencil or pen & ink sketches; a hand-drawn map or poem. Cards, letters, newspaper clippings and photographs were also found tucked in amongst the pages.

I think what is unusual about my Uncle George, as a veteran, is that he was always willing to talk about his war experiences, unlike a lot of people that lived through WWI and subsequent wars. He would often go, mid-conversation, to his study and get one of the dozen or more diaries he had kept during his time of service and refer to them, recalling men he’d served with, things they had seen and done and talked about. His diaries were rich with detailed text written beautifully with a fountain pen; pencil or pen & ink sketches; a hand-drawn map or poem. Cards, letters, newspaper clippings and photographs were also found tucked in amongst the pages.

After his death in 1983 my cousins donated all their Dad’s diaries along with many photographs and memorabilia to the Manitoba Archives, where they are available for all to read. His “fonds”, as the Archives calls personal possessions, consist of diaries, correspondence, photographs, film footage and other records from his career in the Canadian Light Horse Brigade during the First World War.

Here are just a few excerpts of his diary entries, taken from blogs posted by the Manitoba Archives:

Vimy Ridge

April 09, 1917, the first day of the battle. “Monday morning exactly at 5:30 the bombardment started in earnest – every gun at once and the effect was most wonderful – Fritzes’ line was being blown in all directions and in a few minutes over came enormous strings of Fritzes with gestures of putting up their hands – our boys crowded to meet them and one young fellow I saw had his helmet snatched from his head before he even got near our trenches – for a souvenir. After an hours terrific pounding we opened up with the machine guns – the barrage lifted to farther back on the lines of trenches and our boys came streaming across the top mostly in a leisurely happy humour – possibly due to their rum. We could see thousands of men as far as eye would reach on the rolling ground all headed in one directions walking leisurely enough with their rifles slung on their shoulders and their long hungry looking bayonets protruding above their heads.”

“April 13/17 We hold a machine gun outpost on the high road leading from Vimy down to the Douai plain…We are in a German dugout under the road and have a brazier going – cold… Tonight an Imperial officer…halted at our gun. I was down in the dug out. The officer was a lord or Duke or something and when he found we were only privates he wouldn’t talk to us. He asked for our officer…we showed him where we were on the map. But as we were so much beneath his rank he would not believe us. He was well over a mile off course and on quite the wrong road. But no sir we could tell him nothing…the way he snorted ‘Canayedians’ showed extreme contempt for us as colonial troops. As he would not believe us he went up and gave his men orders to march and they went northeast into the night and right into the German lines. In about ten minutes we heard a fracas of many machine guns as the Imperials were all either wiped out or captured. (Later) we learned that there were about two hundred men taken prisoner that night.”

The day after writing that entry Uncle George was released from his temporary assignment to a machine gun brigade and returned to the Canadian Light Horse Brigade, where he remained for the rest of the war.

Passchendaele (Third Battle of Ypes, 31 July – 10 November 1917)

The main thing about Passchendaele, backed up by Uncle George’s writings, was the mud!

“A most beastly hole – mud about a foot deep everywhere – tent pitched on very damp ground and frogs beetles and bugs galore infest the place. The horse lines are paved with brick but everywhere else the mud is fierce – the ditches are all full of water…”

The last battle that my Uncle George fought in was the battle near Iwuy, France on the 11 October, 1918. He was still only 21 years of age. As a member of the Canadian Light Horse Brigade he road into battle on his horse, Nix. Nix was shot and killed almost immediately. Uncle George found himself on the ground, his comrade to his side dead, along with his horse. As the German machine guns rained bullets down on them, those that were not killed rushed the enemy lines, armed with swords. They somehow managed to win that battle and capture the slopes near the town of Iwuy from the German forces. But, at what cost?

In 2018 the town of Iwuy, France held ceremonies to mark the centenary of the final battle there. My cousin Ruth Breckman (Uncle George’s daughter), her husband Kris, some of their children and grandchildren went to France to attend the ceremony. They said it was extremely inspiring and they felt the gratitude of the people there, despite 100 years having passed. The CBC published an interesting article about it: Manitoba family honoured by French town’s celebration of 100-year-old battle.

In 2018 the town of Iwuy, France held ceremonies to mark the centenary of the final battle there. My cousin Ruth Breckman (Uncle George’s daughter), her husband Kris, some of their children and grandchildren went to France to attend the ceremony. They said it was extremely inspiring and they felt the gratitude of the people there, despite 100 years having passed. The CBC published an interesting article about it: Manitoba family honoured by French town’s celebration of 100-year-old battle.

I think it’s wonderful that my Uncle George kept these diaries. They offer a first-hand account of a dreadful time in world history, but also offer an extremely personal glimpse into the life of a WWI soldier. I would encourage anyone who lives in or visits Winnipeg to go to the Manitoba Archives once they re-open to the public and read some of the personal accounts held there, not only from my Uncle George, but many others as well. It’s a reminder that the true cost of war isn’t just dollars and cents and is fascinating stuff!